What follows is a long-winded announcement for a new chapbook from HM, with some additional information on the topic it addresses appended...

Printing a few ‘special’ copies on blue paper was clearly inspired by artists who had begun using it for drawings and prints, experimenting with the tonal effects that could be achieved. Using it for type quickly spread from Adlus to other printers in Venice, then across Italy & into France over the next century, and then to other European printing centers through the 19th century. But it seems to have largely died out during the 20th century; I’d have thought the fine press revival of the early 20th century would have been ripe for blue copies, but seems not. The use of special, or at least different, paper for a few copies persisted, but not blue so much. Corvinus Press issued a few copies of Lawrence of Arabia (1936) on blue paper, but also used three other papers for the edition, which makes the blue variant a little less notable.

Incline Press printed a small volume on blue paper in 2013, celebrating Boccaccio’s birth, but it seems the entire edition of 250 copies was printed on the same paper, so not just a few special ones.

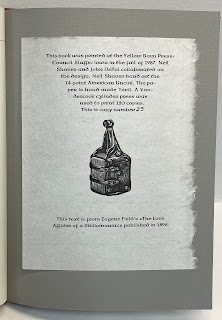

A forged blue copy Aldine! I’d have thought the easiest way to forge a blue copy would be to simply dye the sheets of a regular copy, but apparently this an actual printed forger. Seems a lot of effort.

PrPh Books has issued one catalogue devoted to blue paper copies, and another catalogue with many examples included. Lots of great images. The book above is the first and only edition of the heroic poem that recounts the true events of a duke’s fall from his horse during a tournament, said duke being the author’s patron. Ripe for translation & reprinting.

.%20Metamorphoses%20in%20Italian.%20Le%20trasformationi.%20Translated%20by%20Lodovico%20Dolce%20(1508-1568).%20Venice%20Gabriele%20Giolito%20de'%20Ferrari%201553.%20Christie's.png)

%20Lost%20Time%20Books.png)

%20Amazon.co.uk%20Home%20&%20Kitchen.png)