All the copies of About Agrippa (A Book of the Dead) - A Bibliographic History of the Infamous Disappearing Book have been stitched up, stuck in the printed wraps, & distributed to the many people who helped with the research. That finished something that started in 1992 when I saw an advertisement for the "book" in an issue of Science Fiction Eye magazine.

In 1992 publisher Kevin Begos Jr, author William Gibson and artist Dennis Ashbaugh collaborated on a project that anticipated the advent and impact of digital books. The project, titled Agrippa (A Book of the Dead), has enjoyed perhaps one of the most lively and well-documented online afterlives of any late 20th-century book, particularly for one which so few people have ever actually seen, and which so many people believe does not actually exist.

While the collaboration’s initial concept – a digital text that irreversibly encrypts itself during the first reading, making it subsequently inaccessible, paired with light-reactive etchings that degraded over time – and influence have been thoroughly examined by academics, bibliophiles and Internet trolls, the story of its actual production has never been told in one place. (The term “book” is used here to describe the collective parts, including the 3.5-inch computer diskette secreted in a hallow at the back of the book’s text block). Many of the details about its production have come out only over the past decade, as several major institutions acquired archive materials from the project, and devoted attention and resources to chronicle the book’s creation.

The University of California Santa Barbara hosts an excellent and extensive site called The Agrippa Files, but it was written by academics, and their focus and interests are not the same as a publisher/printing geek, so some details about Agrippa’s tangible aspects remained opaque, if not absent altogether. This is what sustained my curiosity since seeing that ad in SF Eye: there's nothing I find more fascinating than a book about whose existence there is some dispute.

The unexpected appearance of an almost complete copy of Agrippa at my home in 2013 was all the push needed to start trying to piece together the story of its publication. While some fundamental questions remain around exactly how things unfolded as they did, About Agrippa... succeeds in irrefutably confirming that publication happened, though not exactly as promised at the time or described by the collaborators since.

Transcripts of Gibson’s poem appeared online soon after the book’s launch in December, 1992 (thanks to a surreptitious video recording of the disc being run for the publication launch), but people questioned whether the book object had actually been produced (because so few people ever saw a copy) and whether the self-encrypting disc had been created. Doubts about Agrippa’s existence grew in the years since its publication, in no small part due to misinformation (whether intentional or not) from the three collaborators. Gibson has been quoted in several instances saying the project “never happened” and that he’s never seen a copy (but we know he has seen, at the very least, the copy held at the New York Public Library). In the section of Ashbaugh’s Web site about Agrippa, he includes aspects of the production that we know were initially planned but ultimately not achieved (most notably the light-reactive etchings). Begos’ descriptions of the editions published are vague, particularly with regard to the $7,500 “deluxe” issue of 10 copies; he also mentioned “artist’s proof” copies at one point (and he states that both Gibson & Ashbaugh received their A.P. copies in 1992). Questions sent to each of the three collaborators for the article went unanswered. The printers of the etchings and the letterpress, however, provided some new and valuable details about the project via email and postal correspondence.

Perhaps the biggest mystery in the tale of Agrippa’s production is exactly what happened to the Small Edition, which was to have been issued in an edition of 350 copies. We know it was abandoned, perhaps even before the December, 1992 launch event in New York City. At that event Begos reported that copies of the Small Edition were for sale at the Met’s mezzanine gallery. (He also stated the Deluxe Edition was almost sold out, although we know that text and prints for fewer than half the planned 95 copies had been printed.) Five copies of the Small Edition can be traced, but they are not identical: one was issued with the printed sheets torn into leaves, the etchings reduced and reproduced with a photocopier, clippings from a 1938 newspaper randomly inserted throughout, and the whole thing stuffed into the case binding, like a folder (shown below). By April, 1993, the Small Edition is no longer mentioned.

About Agrippa… attempts to trace the production of Agrippa’s physical parts - the text pages, the intaglio prints, the binding, the box. Publisher Begos succeeded in attracting extensive mainstream media coverage for the project prior to publication, and these articles provide insights to how aspects of the initial concept changed or disappeared during 1992. The prospectuses and notices he issued notably lack bibliographic details like edition size and descriptions of the different states being issued. With access to copies of both the Deluxe and Small editions, interviews with a key participants in the production work, and cross-referencing a wide variety of interviews, catalogue descriptions, and print articles, a more clear picture of what exactly was - and was not - issued appears: Agrippa was published (though not exactly as planned), copies do exist (though there does seem to be much variety in their exact details and completeness), and we can trace for certain two copies sold on the market since 2010 (for wildly different prices).

"Begos has spoken extensively about why the book was what it was. Ultimately Agrippa, like many artist’s books, was an interesting thought experiment but the thing itself was practically inconsequential. The discussion it generated is almost entirely centered on the concepts it challenged – ownership versus experience, digital vs physical – and not at all on the design or the (written) content. The message was entirely in the (lack of) medium. The box was hard to store (it couldn’t be put on a shelf with your other books, upright); the book was simply a portfolio for the prints and disc – there was nothing to read; and for most book collectors the paradox posed by the project – to own it or experience it – proved easier to resolve by ignoring than engaging."

About Agrippa... consists of a main article (approx. 10,000 words) recounting the initial plans for Agrippa’s physical parts, and detailed descriptions of (and differences between) copies issued. Interviews with several key participants add context to the technical challenges faced, and how these were resolved (or not). The essay is accompanied by marginal notes with commentaries, expansions, digressions & sometimes subjective editorializing (like the excerpt above) on details, contradictions and inconsistencies in the main text. Numerous original photographs of Deluxe and Small edition copies are included. Appended are a select bibliography of other publications from Begos, a facsimile resetting of a prospectus of which only one copy is known to exist, and a detailed list of references. Here's the Table of Contents:

Source Files

The Artifact

The Concept

The Paradox

The Publisher

Confusion

The Edition[s] As Planned

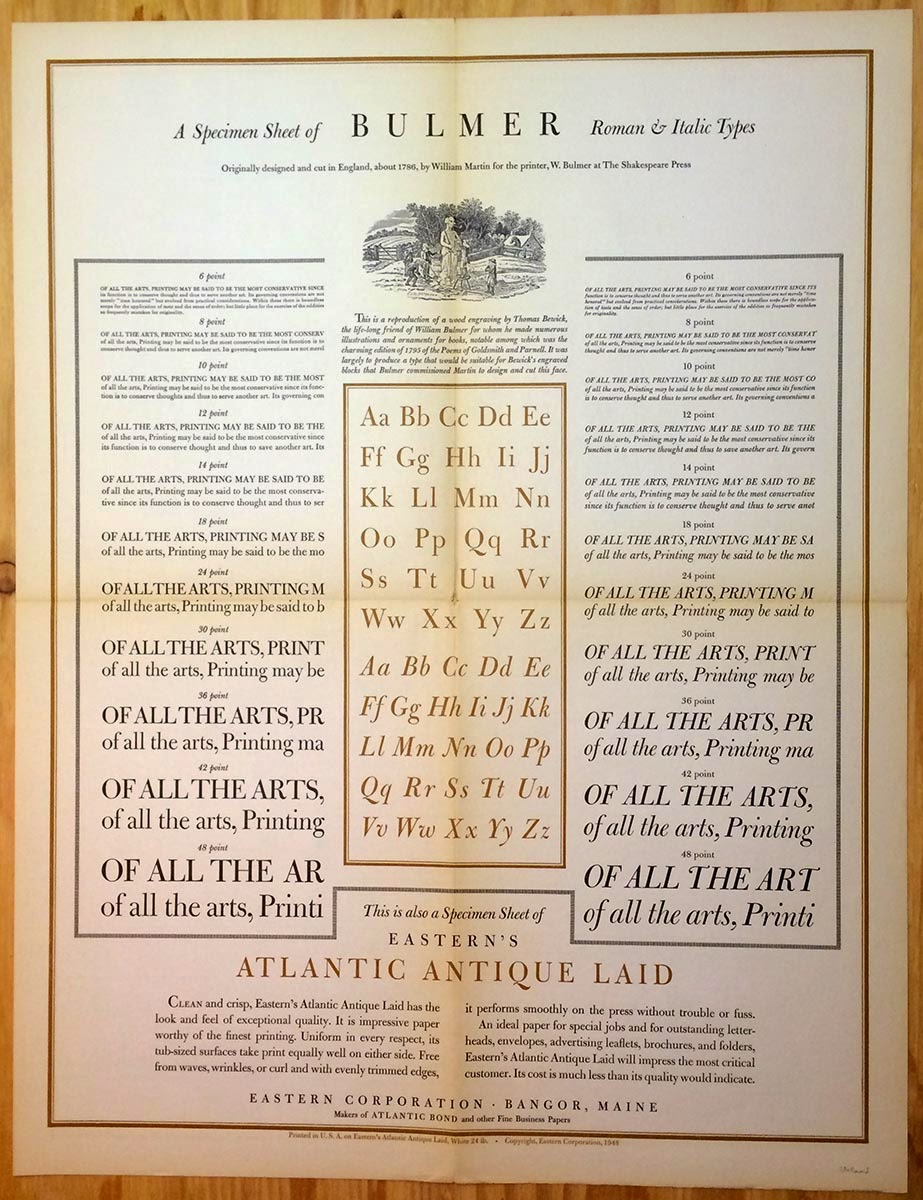

Typography & Letterpress

The Deluxe Edition [As Issued]

What About the “Super-Deluxe” Copies?

The Prints

The Small Edition [As Issued]

How Many Copies Are There, Really?

Follow The Money

Afterlife

About Agrippa... is 8.25-by-11.5 inches, 40 pages, printed in full color, sewn in sections and put into a stiff paper cover. Fifty copies were produced, with most being distributed to people and institutions who assisted in the research. Fewer than 20 copies remain, available at $50 plus shipping.